This article presents a nesting record of the The Barred Eagle-Owl Bubo sumatranus sumatranus. The species has a wide range from Myanmar, through Thailand, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia and Singapore. It can adapt to the widespread monoculture habitat of oil palm plantations and is of least concern. Still it is a striking looking owl and a pleasure to see.

Motivation

In December 2011, I came across a nesting pair and referring to The Birds of the Thai-Malay Peninsula and in correspondence with David Wells I realized that although not an uncommon owl, not much basic information was documented. There was no information on sexual dimorphism, clutch size, brood size, incubation period, development period, parental care and so on. So this then became the basic motivation: to try and add as much knowledge as possible about this species which was first described by Raffles in 1822.

Location

The nest was in a planter box on the highest floor of the Le Grandeur Palm Resort, Johor, Malaysia. The planter box contained bougainvillea. The owls made no effort to improve the nest site, laying the egg(s) directly on the planter box soil. The management and staff of the hotel were kind enough to allow me to monitor the nest activities.

Method

Realizing that all the important activity would occur at night, and the location was quite some distance from my home, the only viable option was to record video for later analysis. I selected a standard surveillance camera and digital video recorder, as the camera was weatherproof, and the recorder would be able to record 24/7 for at least a month without intervention. The camera had infrared capabilities so was able to record at night as well, although in black and white. The quality is fairly basic but proved to be adequate for noting the major activities. High definition recording would have been wonderful but well out of budget. We augmented continuous recording with 14 visits to the site, several at night, for more personal observations. It turns out to have been a good decision to use unobtrusive video recording equipment as the night visits proved the adult owls would simply not visit the nest if there was any sign of disturbance. Following are a series of observations.

Sexual Dimorphism

We found quite a difference in appearance of the adult male and female in this pair. From the behavior of other species of owls it can be established that the bird on the nest brooding the chick in the early days would certainly be the female. With this established we can look for differences between the male and female plumage. There was a noticeable size difference, but this would be hard to see in the field unless both adults were together. Here is a table of the differences.

| Female features | Male features |

| Distinctly dark edge or disc to pale face | Absence of face disc |

| Rufous-brown breast patch with thin barring | Darker breast patch with heavier barring |

| Thin spotty dark barring on lower belly & breast | Thicker more continuous barring on lower belly & breast |

Since this is a sample size of only one, whether one or more of these features can be used as a reliable guide to ID the sex of the bird in the field needs to be determined with more study of birds where the sex is known.

Basic Data

Our first observation of the nest was on Dec 3, 2011 and first video recording was obtained on Dec 9 and first still photos of the chick on Dec 15. From the size of the chick on Dec 15 it was estimated to be 2 weeks old max on which would put the hatch date at not early than Dec 2. Eventually the chick fledged on Jan 30, 2012 which gives a development period of 60 days from hatching to fledging. I recorded video on 49 days, missing a few days due to various human activities yielding over 1,000 hours of video in just less than 1TB of data.

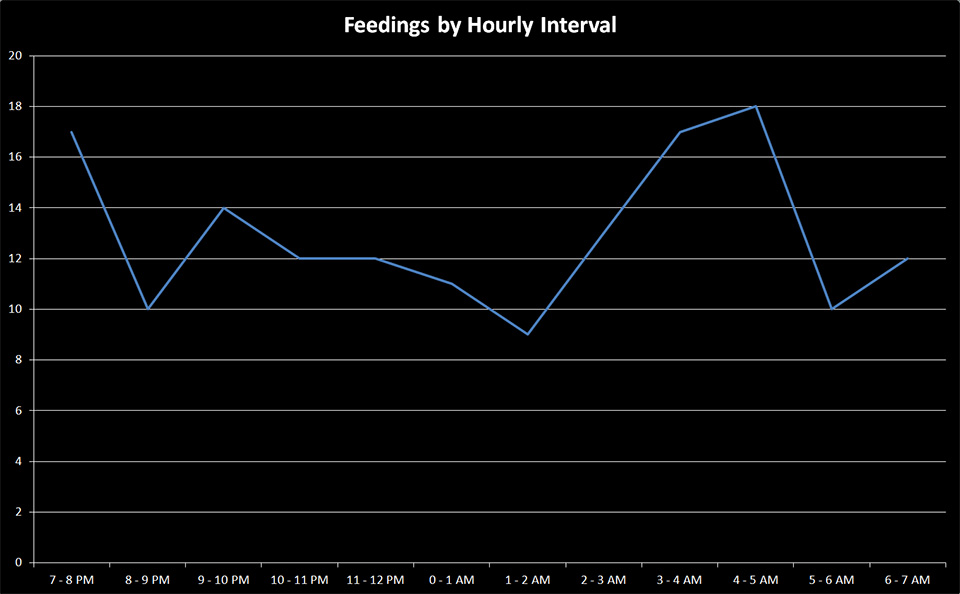

Feedings by Hourly Interval

During the 49 days recorded there were 155 feedings noted for an average of 3 feedings per night, with an observed minimum of 1 and a maximum of 8. Some feedings were quite long, tearing up a rat slowly and feeding it to the chick over 30 minutes. Some feedings were quite short, just a couple of minutes for the adult to pass the chick a prey item that could be swallowed whole. While the female was still brooding the chick she would continue to stay on the nest to brood after feeding. However after the brooding period was over the adults would usually leave the nest as soon as feeding and some grooming was done.

With sunrise and sunset at about 7am and 7pm at this time of year, all feedings started in the dark or twilight. The earliest a feeding started was at 7:17 pm on Dec 10 and the latest a feeding ended was at 7:19 am on Jan 6. In general the feedings started earlier in the evening when the chick was younger and became progressively later as the chick got older. The chart below doesn’t show a strong trend in feedings except a bias to early feedings just after dark and then a peak in the late night.

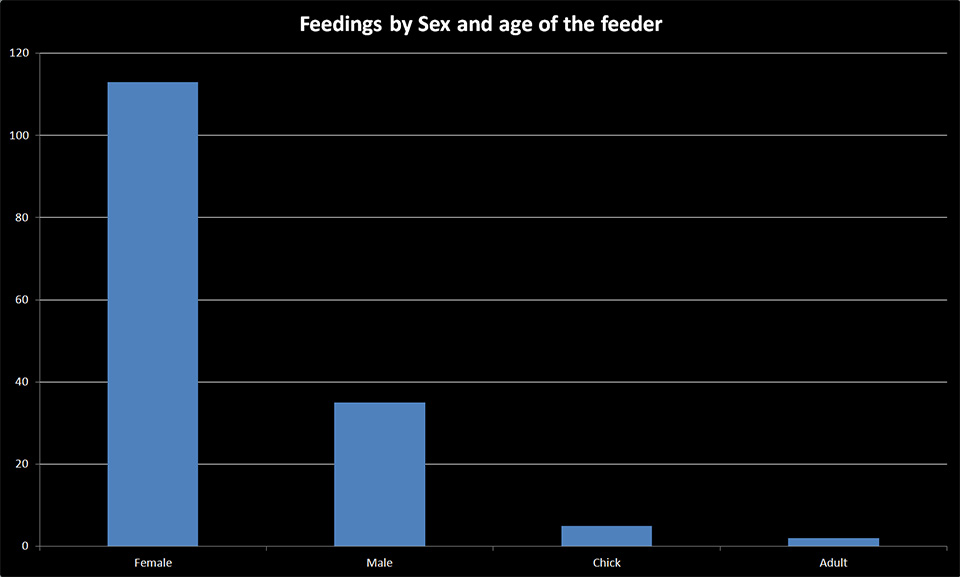

Feedings by Sex

During the early phase of the chick’s development the female was the sole feeder of the chick. Not that the male didn’t share in the work, he often (18 times) brought food to the nest, but this was taken by the female and then feed to the chick. At no time during the early development did the male ever come to the nest without the female being present. This changed on Dec 26 (development day 25) when the male flew into the nest in the absence of the female and fed the chick. Thereafter the male was allowed to come and go to the nest alone. In a few cases the chick feed itself scraps of leftovers, and in a few cases the sex of the adult couldn’t be determined.

Brooding Ends

During the early development days, the female spent most of the time on the nest brooding the chick at night, leaving the nest only for short periods. However, during the day she was on the nest continually from dawn until dusk. Periods of absence during the evening progressively became longer the older the chick became. Finally on Dec 24 (development day 23) she flew off the nest at 8 am and didn’t return until after dark. There was a transition period of a few days where she on occasion did spend time brooding the chick during daylight, but this came to an end three days later, from then onwards the chick was alone during the daylight hours. Of course the adults where in nearby trees monitoring the chick’s safety. The end of the brooding period also coincided rather closely with when the male was allowed to visit the nest unattended.

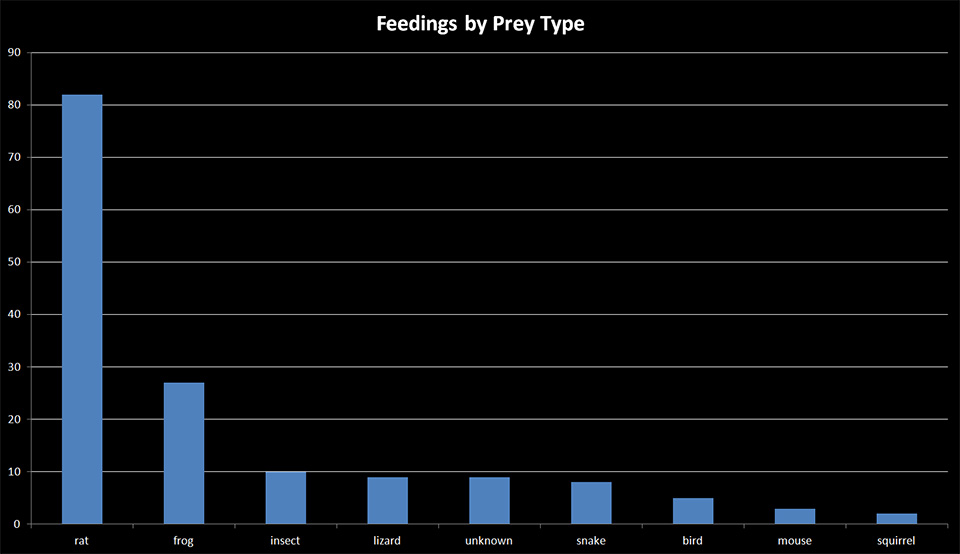

Feedings by prey type

By far the most common prey was the rat. Feeding the rat to the chick was a rather lengthy process, as it had to be torn up piece by piece and feed one mouthful at a time. This could take 30 to 45 minutes if the chick was hungry and kept eating. The second most common prey was frog (sp?). As the chick got older, it was able to eat a frog in one mouthful, so the feeding time was rather quick, just a few minutes. Most of the frogs were fed live to the chick. The rest of the prey items were varied but infrequent, from large insects to birds and squirrels. Snakes were fed live to the chick and could also be swallowed whole.

Family interaction at the nest

When the female brought food to the nest, she generally gave a series of chattering sounds which seemed to encourage the chick to eat. After feeding the chick she would normally groom it for several minutes and then perhaps brood it in the earlier development phase. When the male brought food to the nest usually the female would take it from him, and groom him; and then there might be some mutual grooming. The male would often make a series of barking calls, and the female her chattering calls. Occasionally the female would make a longer call. As dusk fell, she would often make this call and similar calls could be heard in the distance. It seems that there are several pairs of owls in the vicinity.

The chick would sometimes make a soft chirping noise, and would clack its beak making a clicking sound. The nest area was kept remarkably clean, dead carcasses could be seen being removed from the nest. And the male could be seen to be actively doing housekeeping around the nest. A link to video clips illustrating these behaviors are given at the end of this article.

General activity of chick leading up to fledging

During the earliest developmental days the chick barely moved from where it must have hatched. As you can see from this photo on Dec 15 (development day 14) it is still quite small and not very mobile.

By Dec 28 (development day 27) the chick would stand upright and preen itself and was no longer being brooded, but it still hadn’t moved from where it was hatched. You can see it is in the same position relative to the bougainvillea vines as in the first picture.

By Jan 4 (development day 34) the chick was beginning to move around the planter box a bit, just a couple of feet either side of its hatching location.

By Jan 20 (development day 50) the chick was quite mobile, moving up and down the 15 foot length of the planter box and flapping its wings vigorously.

The chick’s activity level during the night continued to expand until just a couple of days before fledging it would range to the adjoining balcony and often make strong wing flaps. But during the day, it would still lay down to sleep. It was observed learning to be fed while perching on a swaying bougainvillea vine, and learning to rest while perched upright. It fledged around 5 pm on Jan 30 (development day 60). It fledged by simply half hopping and half flying from the balcony to an overhanging tree branch. The picture below was taken the day after it fledged.

Discussion

It was fascinating to observe the development of the chick. After fledging the juvenile spends the next several months being attended to by the adults and learning to hunting. As the next breeding cycle begins the juvenile will be driven off or disperse to make room for the new family. In the 2012 breeding season the adults were about a month earlier, and the chick fledged on Dec 24 with a similar (estimated) developmental period. This is now the fourth year this pair have had a single chick. It is hoped that in the future we will actually be able to observe the egg(s) and if possible time the incubation cycle and observe the hatching.

External link to video clips

A series of 15 Barred Eagle Owl video clips is hosted on YouTube at the Barred Eagle Owl videos playlist.

Two audio clips were also uploaded to Xeno-Canto.

Authors & Publication

Several of us collaborated on this article: Con Foley, Lau Weng Thor, Lau Jia Sheng, Tan Kok Hui.

A version of this article was published in BirdingASIA, Number 19, June 2013. BirdingASIA is a Bulletin of the Oriental Bird Club.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the management and staff of Le Grandeur Palm Resort without whose permission and assistance this nest observation would not have been possible. We would like to thank David R. Wells for his helpful input in preparation of this article. We’d also like to thank Kelvin Lim at the Raffles Musem of Biodiversity Research for his help reviewing skins.

Literature cited

Wells, D.R. (1999). The birds of the Thai-Malay Peninsula, 1. London: Academic Press.

Hi Con,

That was a great field report. BTW, since most of the feeding time starts at night, it would be interesting to know which type of birds which the parent owl catches during those hours.

Cheers

Ronnie

Hi Ronnie,

From remains left in the nest we could determine the owl took Black-naped Oriole and feral pigeon as prey. Perhaps other species, but at least those two. I’m sure the owl could easily find where the birds are roosting at night and take them while they slept.

Cheers, Con

Thanks for the info and the nice photos of the owls.

Cheers

Ronnie

Dear Foley,

Very interesting notebook. How about rat? What main species the birds consumed?

For the larger preys etc. Rattus spp. and frog, do they dismembered or decapitated of preys?

How may i cited this notebook?

Hi CM Rizuan

From the remains in the nest the owls took Black-naped Oriole and feral pigeon as prey. These birds were common around the hotel. They might opportunistically take other birds. For the rat (I don’t know what species of rat) they ripped the rat apart with their strong legs and beak before feeding to the chick. The frogs (or toads) where rather small and they attempted to feed to the chick whole.

You may cite this as any other web material. Reference, Author Name, Link to Article, and Date Downloaded

Cheers, Con Foley

Hi Con et al,

Thank you for such a comprehensive report on the owls.

Kind Regards,

Weng